Charles Marsh, in his book Strange Glory, contends that Bonhoeffer was celibate, using as evidence a prison letter Bonhoeffer wrote to his best friend, Eberhard Bethge. In this letter, Bonhoeffer notes that he has had more experience of life than Bethge, except for one thing. Marsh interprets that "one thing" as sex. Yet the context of the letter indicates that Bonhoeffer means marriage, not sex itself.

Bonhoeffer's book Creation and Fall, published roughly a decade before the prison letter, however, suggests that Bonhoeffer may indeed have been celibate. This book, based on a series of lectures on Genesis 1-3 that Bonhoeffer gave at the University of Berlin, explores creation, the Fall, and the expulsion from the garden of Eden.

In Creation and Fall, Bonhoeffer pits humans as imago dei, created in the image of God, bound to and guided by the Creator, against sicit deus, humans acting as if they were God. Sicit deus ignores humankind's inherent limits, doesn't depend on God and acts out of its own resources.

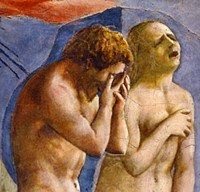

For Bonhoeffer, sexuality expresses this post-lapsarian sicit deus or denial of limits. In contrast, the world he imagines in the garden is asexual. Adam, the man, whose point of view Bonhoeffer identifies with and expresses, respects the physical limits of Eve. They can be naked together because Adam will never violate Eve's body.

|

| "Nakedness is innocence," wrote Bonhoeffer. |

Bonhoeffer expressly identifies the Fall as "the problem of sexuality." (122) For after the Fall, Adam transgresses the boundary and wants to possess Eve's body. This "denies and destroys the creaturely nature of the other person." Thus,"sexuality is a passionate hatred of any limit" (Bonhoeffer's italics). Sexuality "lays violent hands on the other person" and "hates grace." (123)

"Sexuality," Bonhoeffer summarizes, "[is] a perversion of the relation of one human being to another." (125)

This view of sex may startle us in the 21st century. It presupposes a sexuality based on dominance and submission, not mutuality. As with the senior Bonhoeffer's romanticized portrait of their home, it hints that we are entering a different way of seeing. I try to be conscious that I am always viewing Bonhoeffer through a lens slightly blurred by my experience as a person born after the end of World War II.

If Bonhoeffer viewed sex as a problem, as a violation of the Other, does that mean he remained celibate? Did these views change over time?